Speak to an Expert

admin@eumediation.net

Posted on: November 11th, 2024

By Dr Mike Talbot, EU Mediation CEO and Founder

As the dust settles from the US election, I was thinking about how this process might help us think about conflict. I was wondering if there are parallels with the kind of win-lose contest we have been seeing over past weeks, and the kinds of disputes that people encounter every day.

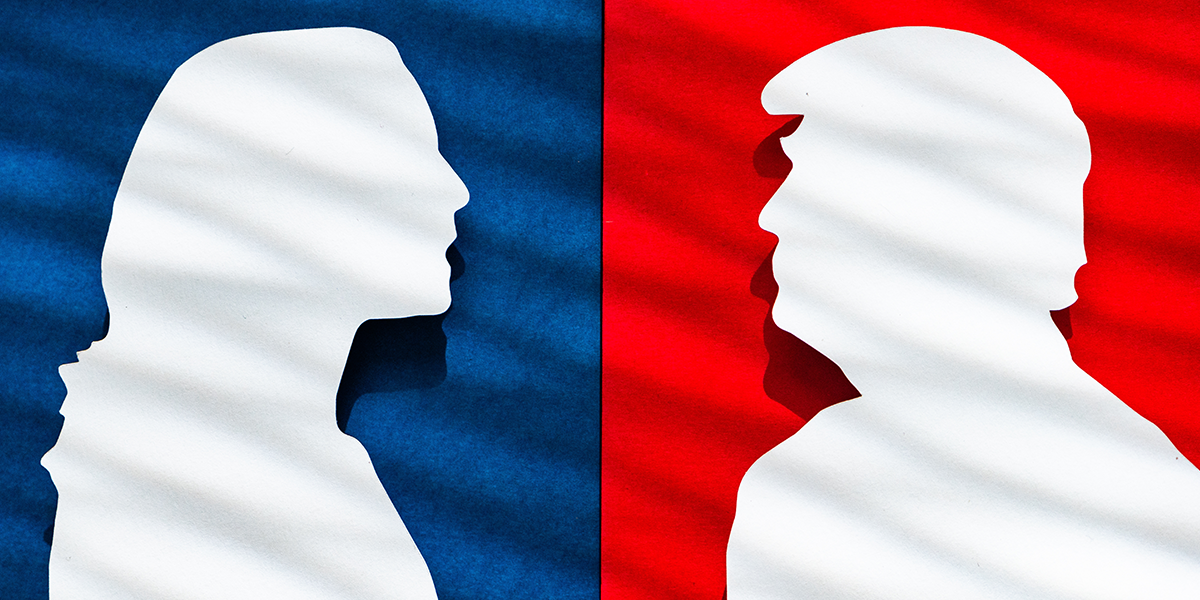

And while an election is of course not quite the same kind of conflict that mediators like us deal with week in week out across Europe, there are quite a few parallels to draw. A workplace dispute, commercial argument, or even family fallout are often characterised as adversarial relationships between two people, and are seen by the disputing parties as something that has to be won. The US election either is, or at least its players like to frame it as, the same kind of thing.

So, how the characters in the election drama behave, and what sorts of moves, messages, and motivations are involved, can help us gain some insight into the psychological process around conflict and its resolution. Let’s take a closer look.

Personalising the Conflict

It is quite striking the degree to which the US election hinges on personality. The candidates’ seem to spend more time talking about who they are than laying out the policies that they represent and intend to bring to the table should they win. Plus, they put an equal (or even greater) amount of energy into talking about the character of their opponent. The electorate seem to buy into this as well: it’s not Democratic Party vs Republican Party, but Harris vs Trump.

We find this happens a lot in all sorts of interpersonal disputes. Both sides put quite a lot of effort into trying to get the mediator on their side. In doing so, they will often talk about their own blameless character, their own good traits, and if challenged, they will say that they are ‘…not like that’. The disputing parties often believe that the conflict is going to have a winner and a loser, and it is horrible to think of oneself as the loser and/or as the person who is in the wrong. The supposition is that ‘the good guy wins’, and each wants to be portray themselves as that.

Confirmation Bias

Another striking aspect of the US election campaigns has been the degree to which the electorate seems to filter out anything that might potentially change their view of ‘their’ candidate. So, when being interviewed on TV, for example, a voter might be asked whether the fact that their candidate did or said some terrible things might change their allegiance, and the answer is ‘no’. In their eyes, no matter what their champion is alleged to have said done, it wasn’t so bad really, or else the other side has done or said much worse things.

And of course we get this a lot in interpersonal disputes. Disputing parties will come to EU Mediation with their own stories about the other person, demonising them and portraying them very negatively: again personalising the dispute and wanting to win over the mediator. But each side’s story tells of their adversary having nothing good going for them: anything that may portray their opponent in a favourable light is filtered out, and anything, however small, that could potentially make them look bad is amplified and made into a major issue.

Loss Aversion

And then we come to the outcome of the US election: why did the vote go the way it did? Essentially, a lot of voters, whether they agreed with this or that promise, whether they favoured this candidate or the other one, they are currently worse off than they were four years ago. And, although this can be largely blamed on the global recession following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine right after two gruelling years of the COVID-19 pandemic, people are saying they didn’t want four years of more-of-the-same.

And when we are loss-averse, we tend to be more sensitive to the pain of loss. Voters in the US, who were finding being worse off hard to bear, voted for the party (or person) whom they believed would be more likely to prevent any further loss.

And again, we see this in disputes that we work with, perhaps more so when the argument concerns something of value: people tend to fear losses more than they want gains, and will often come to an agreement in mediation where they may not have gained anything. More importantly, they have avoided an ongoing situation where they have the potential to lose something or perhaps to lose anything more than they feel they already have.

So, it has been an interesting exercise to think about these two things: how we can distil from the US election some general reflections about conflict resolution, but also how I can try and write impartially about such a divisive topic!